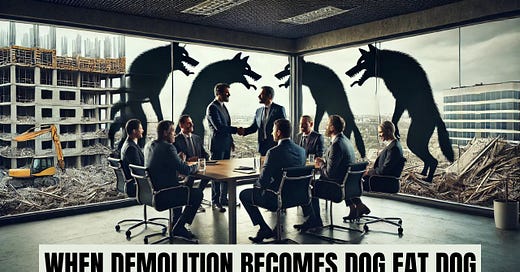

Dog Eat Dog

When the feast of work gives way to economic and workload famine, demolition and construction companies begin to eat each other.

There are, apparently, seven stages of grief: shock, denial, anger, bargaining, depression, testing, and acceptance. Personally, in my own dealings with grief, I have generally gone from denial to depression, skipping all the other stages. I did not pass go. I did not collect £200.

It occurs to me that the demolition and construction industry’s response to a downturn in workloads or a wider economic recession follows many of those same stages. But there is one notable difference. Rather than acceptance, there is cannibalism. I’ll get to that in a moment. But let’s start with those other stages.

Appropriately, the most surprising response to tougher times is shock. Quite how anyone is shocked by a downturn in this industry is beyond my understanding. Ours is a cyclical industry in which good follows bad, highs follow lows, tick follows tock follows tick follows tock. Wherever we are on the industry’s fortune cycle, look back five or ten years and you’ll see precisely what will happen next. And yet, each time the market turns, there are company owners and industry veterans staring at their books as though some divine force has unexpectedly turned off the tap.

Perhaps it’s optimism bias. Perhaps it’s wilful ignorance. Or perhaps it’s the result of an industry that, at its core, does not plan much beyond the next contract. Whatever the cause, companies are often caught off guard, despite the warning signs blinking like hazard lights on a foggy motorway.

I can tell you from experience that the next stage is no better. You can deny it all you wish, but when the industry’s house of cards begins to collapse under its own weight, denial just doesn’t work. There are many who believe they can work their way out of a hole, that they can cut corners to survive, that their past reputation will somehow shield them from the present reality. They tell themselves that the dip is temporary, that things will pick up next quarter, that a big contract is just around the corner. The problem is, so does everyone else.

Of all the stages, anger is perhaps the most understandable. You have worked hard, followed all the rules, abided by the regulations, and kept your nose clean. And then, without warning, some outside influence rips the rug from under you. Maybe it’s a recession. Maybe it’s a change in government policy. Maybe a once-loyal client has slashed their budget, had their head turned, or gone under entirely. You have every right to be angry. Angry at the economists and politicians. Angry at the industry. Angry at the world.

But anger won’t pay the bills. It won’t keep the machines running or your workforce employed. But that doesn’t stop many from railing against the unfairness of it all, even as the walls close in.

The next stage in grief and in construction is bargaining. Your company is set up to demolish tower blocks or to build houses. But with workloads shrivelling and the bills mounting up, there is a temptation to become all things to all men in pursuit of that next paycheck. Suddenly, you’re not demolishing tower blocks, you’re demolishing toilet blocks, just to keep the wheels turning.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with diversification, but there is a problem when it’s done out of desperation rather than strategy. A company built to handle multi-million-pound projects cannot survive long-term on a starvation diet of bite-sized contracts. Overhead costs don’t shrink just because the jobs do.

You have tried everything, and none of it has worked. Little wonder that depression starts to set in. You start to feel empty, deeply sad, and utterly alone. Where you were once gregarious, attending all the industry functions and being an active participant in the sector, you withdraw to lick your wounds in solitude.

Depression in an industry like this doesn’t just manifest in individuals; it spreads across companies like a virus. Morale plummets. Investment dries up. The very people who once saw the industry as a community begin to see it as a burden. When depression takes hold, innovation stalls, ambition fades, and the sector as a whole starts to shrink into itself, waiting for a better day that may never come.

As the recession deepens, no back is left un-stabbed. The industry’s former battle cry of “all for one and one for all” gives way to cries of “every man for himself.”

Testing is the process of trying to find solutions that offer a means of dealing with loss. It is also the means by which companies attempt to diversify, belatedly. Some firms pivot successfully, finding new niches, reinventing themselves in ways that not only sustain them but position them for future success.

But if the entire market is down, there is no diversification to be had. You just find yourself chasing red herrings down blind alleys, throwing good money after bad in the hope that something will stick. And when it doesn’t, the final transformation begins.

In grief terms, the final stage is acceptance. Acceptance does not mean people feel OK about a loss. Rather, it means they realise the loss is their new reality. They understand that while life will not continue as it did before, it will go on.

In demolition and construction, there is rarely acceptance. Instead, there is cannibalism.

A few months before the recession hit, you were happily cross-hiring equipment to local competitors; you were forming joint ventures with other rivals to cope with all the work coming your way; and you were attending industry events - in part - to tell everyone just how well you were doing.

But as workloads ease and margins tighten, you surrender to your base instincts. It begins with bad-mouthing your former joint venture partner to clients, questioning their competence, their health and safety credentials, and their financial stability. It gets worse from there. You cut prices to win the work needed to keep your wheels turning and your men and women employed, but also to ensure that your rivals don’t get the job.

As the recession deepens, no back is left un-stabbed. The industry’s former battle cry of “all for one and one for all” gives way to cries of “every man for himself.”

And then, when the clouds of recession finally begin to part and the sun emerges once again, we are left to count the cost of our oh-so-predictable race to the bottom. An industry divided, many of its number fallen by the wayside, prices that have barely risen in a decade; and a pile of bones as evidence of what happens when the industry consumes itself.

And yet, as predictable as the fall is, so too is the rise. Those who survive will dust themselves off, patch up old alliances (or form new ones), and convince themselves that the worst is behind them. They will forget the lessons, ignore the warnings, and continue as if nothing happened.

Until it does. Again.