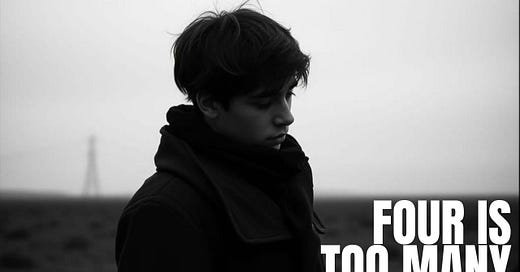

I am 60 years old. My life has been touched by suicide four times.

I didn’t know the first suicide victim that I encountered. I was maybe 11 years old when a man laid down on the tracks in front of a train close to where I was playing football with my friends. I only saw the aftermath. A headless, lifeless body clad in a beige corduroy suit; a large red “V” of blood on his chest.

The second time suicide ripped its way forcibly into my life was when my former business partner took his own life, leaving behind a wife and six children. I had worked with him, on and off, for about 15 years at that point.

My third brush with suicide came when the father of one of my wife’s oldest friends took his own life just a few years ago.

Yesterday, I attended the funeral of a 32-year old man I had known since he was about five. He was my son’s best friend. My son helped carry his coffin as he was laid to rest; a job that no-one in their 30s should ever be required to do.

My relationship with each of the victims was different: from non-existent, to fleeting, to close.

But four suicides across the span of 60 years feels like a lot. That number feels too high. Way too high.

Maybe I have just been unlucky. Maybe that number is an anomaly. Or maybe, I am typical. Maybe the law of averages dictates that we will all encounter suicide a few times in our lives.

Unless we work in the field of demolition and construction, where the rate of suicide is almost four times the national average.

According to the Office for National Statistics, the suicide rate among the general population in the UK is roughly 10.7 per 100,000 people. In construction, that number is 34 per 100,000 people.

Now this is far too serious a subject for overly-simplistic mathematics. But imagine that my four suicides in a lifetime IS, in fact, pretty typical. If you extrapolate that out, you might encounter suicide 13 or 14 times across the span of a demolition or construction career.

Four suicides seems too many for a lifetime. But 14 is unimaginable. Preposterous.

And yet, whenever I speak or write about this subject, it resonates; it strikes a chord of familiarity within the industry.

It would be wrong to say that suicide is so common that it has almost been normalised in the industry. But it is definitely common enough for a very large proportion of the sector to have been touched by it in some way.

It is not a single, catastrophic event like a Grenfell fire or a Didcot boiler house collapse. Instead, it is a slow, incessant trickle. A trickle that happens quietly, in the background. Like the constant drip, drip of water on rock, it erodes. It wears down. It doesn’t make the national or industry news headlines, because each industry suicide is separate and distinct. And yet it gnaws away at the very foundation of the industry, robbing us of valuable workers, and robbing families of husbands, fathers and sons.

And suicide is indiscriminate. When I think about those I have encountered, they were a mix: one was a husband, father and grandfather. One was a husband and father. One was single, seemingly with his entire life ahead of him.

One common trait they all shared is that all four of the suicides that I have encountered were men. Women take their own lives too; I understand that. But this does look and feel like a very male thing. In fact, statistically, men are roughly three to four times more likely to kill themselves than women. And, since demolition and construction remain - stubbornly - male-dominated, perhaps it’s easy to see why this sector suffers more than its fair share of suicides. Maybe this isn’t a construction thing. Maybe it is really a male thing.

None of which makes it any more excusable or palatable. None of which makes it any less tragic.

I keep coming back to that number. Four suicides across a 60-year lifespan.

Last year, there was a question doing the rounds on social media: How many owls would you need to see in a day before suspecting something might be wrong?

Most people said that if they saw one or two owls, they would consider it a happy coincidence; a rare treat. Alarm bells would start ringing if they saw three or four owls in a single day. Repeated exposure to seemingly rare events (like owl sightings or suicides) potentially signals a deeper issue.

When I saw the aftermath of my first suicide, I went back to my football game with my friends and we barely spoke about what we’d seen. Having now seen four, my alarm bells are ringing. Loudly.

The COVID-19 pandemic is estimated to have killed more than seven million people worldwide. That pandemic brought the world to standstill and was the only talking point - publicly, and in the media - for roughly two years. I knew only two people that died as a result of COVID, half as many as I know that have been killed by suicide.

And still I return to that number. Four suicides across my 60 years. It haunts me, not just for the lives lost, but for what it signifies. If this is typical, what does that say about our society, our industry, our understanding of mental health?

How many more must we lose before we acknowledge the silent epidemic taking place around us? The construction industry, with its stoic, macho culture and relentless pace, seems particularly vulnerable. But beyond statistics and studies, these are human lives: sons, fathers, friends.

My son is broken by the knowledge that he was unable to pull his best friend back from the precipice. In all likelihood, he will carry the weight of that loss for the rest of his life. And that burden will be far greater than the weight of any coffin.

I don’t have the answers; just questions. And the biggest question of all is this.

How can we make it stop?