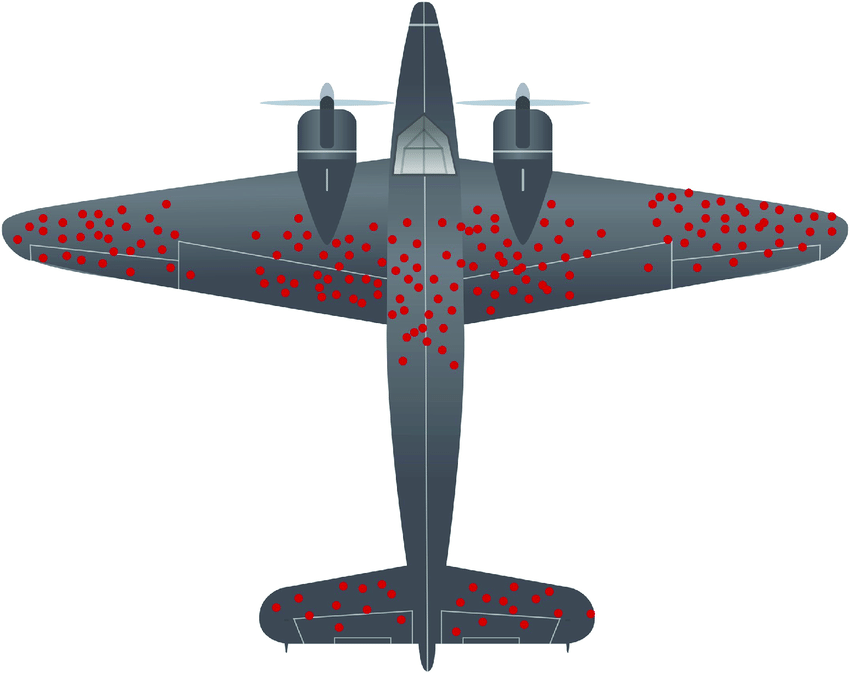

Where the bullet holes aren't

An insistence on accentuating the positive and eliminating the negative means that valuable lessons are being missed in the sphere of demolition training.

At the height of World War II, the British Royal Air Force commissioned a study. The purpose of that study was to understand which parts of their aircraft were hit most frequently by bullets and anti-aircraft fire so those areas could be reinforced to provide pilots with greater protection.

The results were presented in diagram form (above) and appeared to give RAF chiefs precisely the information they had sought.

But a mathematician named Abraham Wald disagreed with the findings. In fact, rather than reinforcing the areas that had received the highest number of bullet holes, Wald suggested doing the exact opposite. The planes studied, he argued, had made it back safely so the damage inflicted was demonstrably not critical. He posited that the planes should be reinforced in areas where the bullet holes weren’t because the undamaged parts of the plane were precisely what allowed them to make it back.

This phenomenon is known as “Survivorship Bias”.

Author Rishabh Nahar says: “It is a tendency to focus on the survivors. After any event that leaves behind survivors, non-survivors are often ignored. If failure becomes invisible, then naturally, we will focus on the success.”

OK, that is the history lesson and the introduction to data analysis done.

So what can demolition or, more specifically, those in the sphere of demolition training learn from all this? I am glad you asked.

Demolition training providers offer training courses and they monitor very closely the number of people sitting those courses. They also monitor the number of competence cards issued to those that successfully complete that training.

Since there is a logical progression through the industry ranks and because some of these competence cards require regular renewal, those same training organisations can reliably predict future demand for refresher courses or competence card upgrades.

And they do so based on the fact that those card holders will remain in the industry, quite possibly for 40 years or more. They can continue to deliver what they believe to be tried and tested training courses and issue competence cards because men and women keep on coming back.

But what of those that don’t? What about those demolition workers that, like those WWII planes, were lost in action?

Modern demolition training is geared heavily towards a rinse and repeat model where courses are delivered by rote and repetition.

The fact that the UK demolition industry employs upwards of 25,000 people – most of them card-carrying and all of them living – suggests that the training they receive is successful.

But what about where the bullet holes weren’t? What does the death of a demolition worker tell us about potential shortcomings in the accepted training regime?

At present, the answer is simply that we don’t know. There have been various attempts over the years at creating a centralised database of accidents and fatalities. The International Powered Access Federation (IPAF) has successfully implemented just such a system and it is used to inform their safety training around the world.

Here in demolition, however, such a notion has never gained traction. Demolition comes over all shy when asked to share details of its shortcomings; even though those shortcomings might actually help save the life of a fellow demolition professional.

To keep tight-lipped about an accident investigation or to ignore its findings is to accept that there are improvements that COULD (and should) be made; but to simultaneously ensure that they won’t.

Trade bodies and training providers apparently have no appetite for such learning. So it must fall to individual companies to learn those lessons and to apply that learning to ensure there is no repeat in the future.

If your company has suffered a fatality and you’re thinking “I have no intention of sharing the details. That would be commercial suicide”, I have two things to say.

The first is that I would ask you to remember how you felt when you discovered that a colleague, friend or even family member had been killed in the line of duty. Do you REALLY want someone else to experience that pain, guilt and sense of loss.

You may have been totally unconnected or legally exonerated of any responsibility in that fatality. Regardless, someone has died. Surely sharing the details of that incident to ensure it doesn’t happen again is not just your duty; it is the VERY least you can do?